In my last blog I wrote about the men of Motown and how their songs taught me it was okay to cry. Today’s blog is about another life lesson I acquired from a singer, James Taylor, whose acoustic guitar-driven songs and gentle voice led pop music out of the revolutionary 1960s into the reflective ‘70s. To me, his Sweet Baby James album and hit song, “Fire and Rain” were a breath of fresh air.

But it wasn’t just James’ musical style that I found appealing. Before first hearing his heartfelt ballads, it was only the women in my world who I saw as gentle and contemplative. Hearing a man tenderly sing about life, though new and different, felt right to me and I paid close attention to his every word. Though only eight years older than me, James Taylor became my musical father.

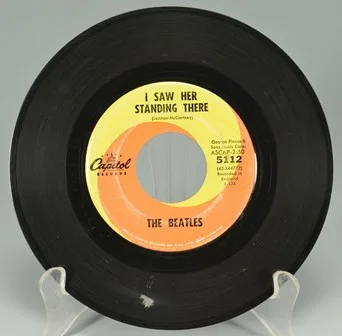

Like a good son, I collected every truth he sang, each record a lesson in a new masculinity: “You’ve Got a Friend,” “Carolina in My Mind,” “Walking Man,” “Shower the People, “Don’t Let Me Be Lonely Tonight.” And then, in 1977, James recorded what sounded to me like his most influential message, the one that would lead me to what I was seeking. He called his song “Secret O’ Life.” Take a listen.

I’m tempted to print all the lyrics of “Secret O’ Life” in this blog because, to me, every word has profound meaning. But let’s start with the opening line:

The secret of life is enjoying the passage of time

What an unusual way to begin a pop song, I thought. Even in my first listen I knew James wasn’t singing about being head over heels in love with his bride, Carly Simon. He was singing about something bigger, something that always seemed just out of reach in my life. At age 22, I was struggling with where I was heading. College had only managed to confuse my career options and I was in the middle of directing a summer children’s camp, responsible for the well-being of hundreds of youngsters and a couple dozen teenagers who were supposed to be their caretakers. I was in over my head and didn’t have a clue what I was doing, which made the second line of “Secret O’ Life” so relatable:

Any fool can do it, there ain't nothin’ to it

Really? Nothing to it? James had my ear, and he sang on:

Nobody knows how we got to the top of the hill

But since we're on our way down

we might as well enjoy the ride

Imagine hearing that advice in your early twenties, when everything you’d been taught about a successful life involved fighting your way to the top, stepping on those you encounter along the way. Yet, wise “old” James Taylor, age 30 when he released “Secret O’ Life,” was telling me it didn’t have to be that way. With my full attention, I considered a few more lines, which hinted at a new life path:

Now the thing about time is that time isn't really real.

It's just your point of view. How does it feel for you?

Einstein said he could never understand it all.

Planets spinning through space, the smile upon your face, welcome to the human race.

To be sure, science was never my strong suit, but with James singing Einstein’s theories, it started to make sense. I listened to “Secret” hundreds of times, feeling its guiding principles seep into my confused thinking. I became curious how others defined the human experience and began reading works by spiritual seekers like Deepak Chopra and Eckhart Tolle. Thanks to James and his secret to life, I began experiencing a new feeling: contentment.

Decades passed and then, about ten years ago, I learned something about Taylor that made “Secret O’ Life,” all the more meaningful. When he wrote the song, James was five years into his eleven-year marriage to Carly Simon. Things looked pretty rosy for the famous couple, but in reality Taylor was regularly relapsing to a debilitating drug habit. His storybook marriage would eventually fall apart and a second one would fail before several attempts at rehab helped him finally beat his addiction. I thought back to those early James Taylor years, now aware that the image of him as a happily married music maker was far from true. He wasn’t some guru sitting in a lofty penthouse preaching life’s secrets; my musical dad had been as messed up and lost as I was.

Understanding that is what makes James’ final advice on “The Secret O’ Life” so poignant:

Isn't it a lovely ride?

Sliding down, and

gliding down.

Try not to try too hard.

It's just a lovely ride.

I’ve forgotten and remembered James’ wise words dozens of times since first hearing it, just like he slipped in and out of his worlds of fame, love and drug dependency. But isn’t that the best thing about a song that has been with you all these years? We lose sight of where we’re heading now and then, but with the help of lullabies of hope like “Secret O’ Life,” we will once again find our way.

?

What song comes along to rescue you now and then?